April is designated as Autism Awareness and Acceptance Month—a time meant to celebrate neurodiversity and advocate for inclusion. Yet, this April was marked by a series of heartbreaking incidents that underscore how far we still have to go in protecting and supporting autistic individuals.

On April 5, 17-year-old Victor Perez, a nonverbal autistic teen with cerebral palsy, was shot nine times by police in Pocatello, Idaho. Responding to a call about a disturbance, officers encountered Victor holding a knife in his fenced yard. Within seconds, they opened fire. Victor succumbed to his injuries after being taken off life support on April 13. His family and disability advocates have rightly condemned the complete lack of de-escalation and the use of deadly force on a disabled child in distress.

Victor’s death was heartbreaking—but tragically, it was just one of a number of lives lost in April. At least five autistic children died this April after wandering from safe environments—many drawn to water, which remains the leading cause of death for children with autism. In Nebraska, 9-year-old Kendrix Brehmer drowned in a lagoon after leaving his school during recess. These incidents are part of a disturbing trend: the National Autism Association reports that eight children with autism have died in 2025 due to wandering, with most fatalities resulting from drowning.

These stories are more than isolated tragedies–they are symptoms of a deeper, systemic failure in ensuring the safety and well-being of autistic individuals. While awareness campaigns and symbolic gestures are important, they must be accompanied by concrete actions: comprehensive training for law enforcement on interacting with neurodiverse individuals, investment in community support systems, and widespread implementation of safety measures to prevent wandering.

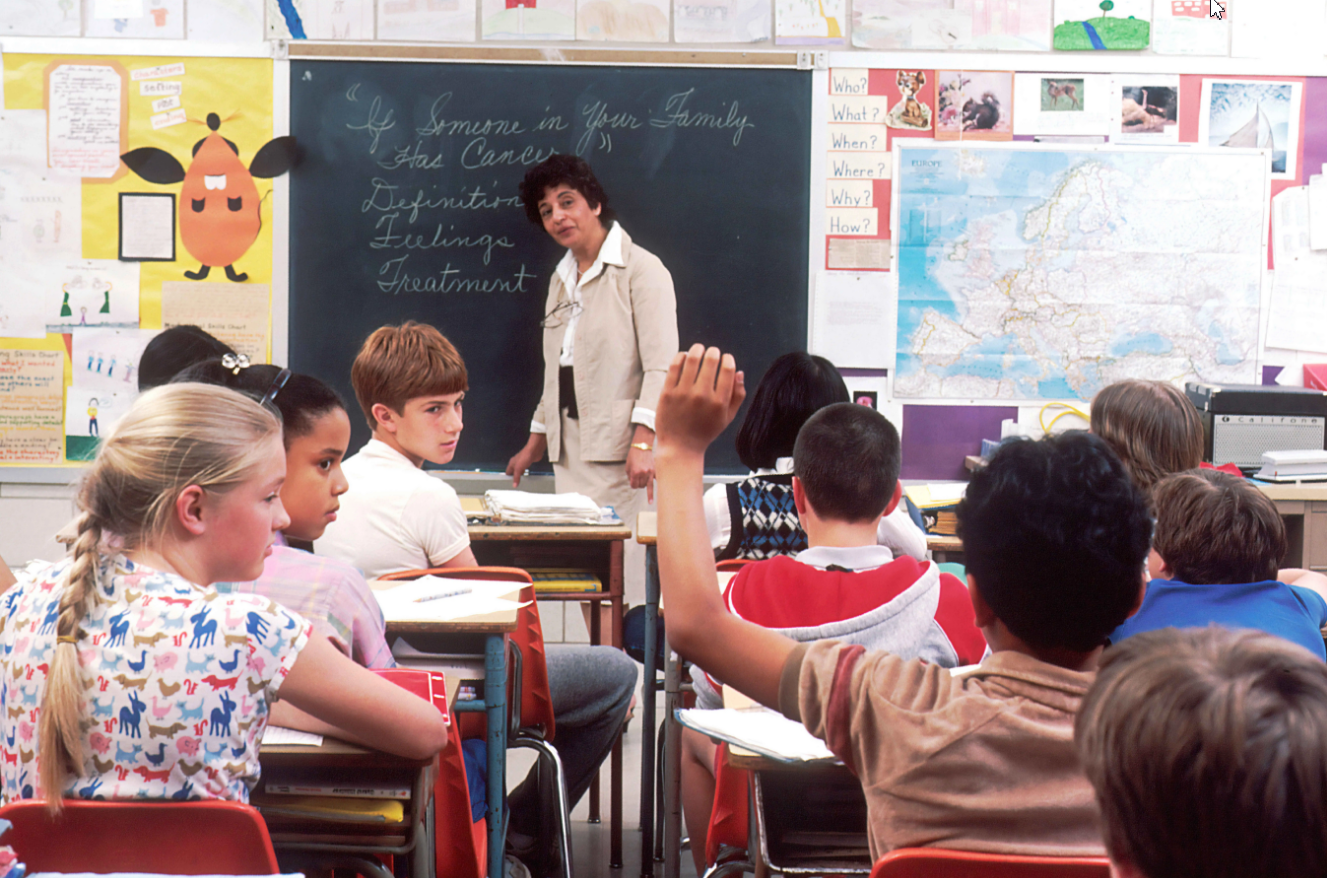

As the need for better training becomes painfully clear, a number of new programs have emerged to help law enforcement officers interact more safely, respectfully, and effectively with people on the autism spectrum:

- Autism Risk & Safety Management: This program offers comprehensive training tailored for first responders, emphasizing the importance of understanding autism-related behaviors and appropriate response strategies.

- VirTra’s V-VICTA® Program: VirTra has developed certified law enforcement autism training curricula, such as the V-VICTA® program, which utilizes immersive simulators to provide officers with realistic scenarios. This hands-on approach allows officers to practice and refine their responses to situations involving individuals with autism, ensuring they are better prepared for real-world encounters.

- IBCCES Law Enforcement Training: The International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards (IBCCES) offers a 2-hour online training program for police teams. This course educates officers on what autism is, how to communicate and interact with autistic individuals, and best practices on safety and de-escalating in specific scenarios. The training was created by experts as well as autistic adults to build understanding, promote empathy, and encourage more positive and effective communication.

These initiatives are important steps. But they are still far from enough.

I spoke about this in my 2018 TEDx talk, and heartbreakingly, we’re still seeing the same patterns today. For real change to happen, these kinds of trainings must become standard across all police departments nationwide–not optional extras, but essential education.

This past April should be a wake-up call. If we say we accept autistic individuals, then we must act like it. That means creating a world where they are not only seen and acknowledged, but also truly safe, supported and valued.

We owe that to Victor. We owe it to Kendrix. We owe it to every family living in fear that the system won’t protect their child.

As we reflect on these tragedies, let it serve as a call to action. The lives lost in 2025 compel us to move beyond awareness and toward meaningful change.